- Home

- R. R. Ryan

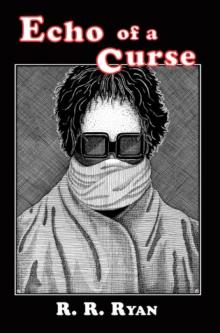

Echo of a Curse Page 8

Echo of a Curse Read online

Page 8

Aunt Charlotte smiled. Mary never forgot her weakness. And following Mary she saw that it was there on a little tray, the sherry; the biscuits in a little silver dish. Evidently Mary had something to tell her; and what that was seemed quite clear to the older woman’s experienced eye.

But she certainly did not expect the story to which she now listened.

“What a disaster!” Aunt Charlotte commented when, with some reservations, Mary had told her tale. “It’s a dreadful, dreadful pity you’re having a child by such a man. I confess I’m not surprised to hear he’s turned out badly. I never did like him. There’s something uncanny about his eyes or mouth or expression; about him altogether, as if, though he’s present, he’s not there . . . As if he’s not quite one of us in spirit.”

These words astounded Mary. Aunt was no thinker, but guided her life by her feelings, yet had expressed in a thinker’s terms exactly what she, Mary, experienced on each occasion she entered Vincent Border’s presence.

“So, Aunty, I’ve had you put into my room. You won’t mind that?”

“It’s not a case of minding. If Mrs. Thatcher’s giving up her double duties—and it’s about time she did, I should say—someone must sleep with you in her place.”

Neither woman had noticed Ruth’s stealing in like an indeterminate shadow to stand and listen with wide eyes and parted lips; and both started when she suddenly spoke.

“Please, Ma’am, please, if Mrs. Thatcher’s not coming any more, won’t you let me sleep in your room? I sleep very quiet and I’d look after you like anything.”

Clasped hands and intensity of pose witnessed to the girl’s sincere desire. In sheer astonishment the visitor remarked:

“Well, I never did!”

“I haven’t explained that Ruth’s my little friend as well as our maid,” Mary said.

But Aunt Charlotte’s lips pursed. She did not approve of any but the usual formal relationship between mistress and servant.

“I shall certainly sleep with you, so that settles the matter.”

“Do you really want to, Aunt? I hadn’t thought about Ruth.”

“If only you would, ma’am,” Ruth interpolated.

There was the deepest feeling in her voice; and of this Aunt Charlotte disapproved.

“It’s plain,” she told herself, “that the child has formed one of those unhealthy adolescent infatuations for Mary. The sooner that’s nipped in the bud the better.”

So she nipped it forthwith, dismissing the matter. But Ruth’s eyes haunted Mary long after the incident ended. She agreed with her Aunt that the misdirected passions of the immature should not be encouraged; nevertheless, there had been a despair, an anguish in Ruth’s eyes that, no matter how foolishly exaggerated it might be, was unquestionably distressing to its possessor.

But Ruth was forgotten during the bustle that usually accompanies an arrival.

“Vin lunches out,” Mary told her Aunt. “I’m having cutlets done in egg and breadcrumbs as you like. After I’ll show you my other presents, shall I?”

“Yes, my dear. You know I shall like seeing them. Did Vin give you a present?”

For an instant Mary hesitated; she had never lied to Aunt Charlotte, but, on this occasion, surely a lie had more virtue than the truth—so she lied. “Terry gave me a dozen silk stockings. Altogether I’ve had twenty-eight pairs. I don’t know how you knew I wanted lingerie, Auntie.”

“My dear, girls always want lingerie.”

“Where did you get such lovely cobwebby things? They’re the most delicate I’ve ever seen!”

“They’re ridiculous as garments, if that’s anything; but I know what you girls are. Go along with you!”

“Well, I’ll show you the rest of my presents.”

However, she had reckoned without Vin, for each treasured stocking was laddered, the cobwebby garments were all cut in small portions. So with everything else. There remained not one present that in some way or other had not been ruined.

Mary stared at the destruction, so opposed to sanity, so opposed to ordinary human behaviour. Anger had no place in her heart; it was occupied by fear alone. She was as sure as that she knelt upon her knees in her own house, gazing at the remains of what had been delightful birthday presents, that Vin would successfully pass any test to which the world’s greatest alienists might subject him. All this was not insanity; it was something else, something explained by that odd obliquity of his nature.

And now a tornado of anger swelled up and burst in her head, so that it took her a considerable effort of will not to voice the imprecations accompanying it.

White with holding back this ever-recurring tide, she re-entered the dining-room not only minus the gifts she had rather unnecessarily set out to bring down, but also minus an excuse for her empty hands; and so her confusion was doubled when Aunt Charlotte exclaimed:

“You haven’t brought the presents!”

Not for a king’s ransom would she reveal the revolting truth. To do so might involve her in various deplorable complications. Aunt’s imagination was limited, but her powers of argument were immense.

“I . . . I’m sorry, Aunt; we’ll leave them just now; would you mind? I’ve been sick.”

Her appearance so bore out her declaration that the older woman burst into a deluge of advice, together with not a little reminiscence.

The visitor did not see her nephew-in-law until breakfast next morning. As she entered in some excitement with the morning newspaper folded back to a certain page and column, he looked up at her, his eyes ablaze with secret laughter. She glanced at Mary to discover whether there was any cause for this startling and inexplicable mirth, but her niece seemed oblivious of Vin’s hilarious condition, and looked up with serious, abstracted eyes.

“Good morning, Aunt.”

“Good morning, my dear. Good morning, Vincent.”

“Good morning, Auntie. You look startled.”

“I am. Have either of you seen the newspapers?”

“I haven’t, Aunt Charlotte. Why?”

“A freak’s escaped from the fair. Listen.”

Even while her Aunt raised the folded paper to read out the news that had alarmed her, Mary grasped the truth. No need to read it out. She knew. Not only did she know, but had known that this would happen, that it was predestined. Her eyes askew with fear, she sat gnawing the knuckles of her clenched right hand, while Vincent watched her, the lambent laughter in his eyes wildly dancing.

“It’s headed: ‘WARNING!’ in huge letters. See! And it says:

“Alarm has been caused by the escape from our annual fair of a mystery freak whose freedom may have sinister consequences. No doubt large numbers of local residents have already seen THE INEXPLICABLE in its cage. The actual potentialities for harm of this amazing creature can only be surmised, since no one knows whether it is human or animal. That it is ferocious and a would-be killer is unquestionable; but it may also be carnivorous.

“Residents are warned to report any sight or sign of this dangerous being. Ring up the police station: 4923 without delay. Hesitation may prove fatal.

“Dr. Julius Erne, who exhibits THE INEXPLICABLE, is unable to elucidate the mystery of how his exhibit obtained freedom. Because of its animal propensities the creature was kept caged by order and the bars of its prison would have defied Hercules himself. The cage door was invariably padlocked and Dr. Erne kept the key on his person. To his knowledge the key has never left his keeping and there is no sign of the lock having been forced.

“It can only be surmised that someone either provided the creature with a key, or deliberately released it and locked the cage once more . . . Unless . . .

“Unless the assumptions of Tiger Hunn, a negro attached to the fair, can be accepted. According to Hunn, THE INEXPLICABLE is neither man nor beast, but something far more terrible . . .”

“All the rest’s a description of the thing. It’s dreadful, isn’t it?”

A curious noise from Border attract

ed both women. His eyes were full of faunlike raillery.

“Please, Aunt Charlotte, don’t say ‘thing’ in that tone!”

“Why ever not? It is a thing.”

“We are all ‘things,’ but this ‘thing’ is a relative of mine.”

“Of yours! Don’t be so absurd, Vincent. What do you mean?”

“I mean that I believe the ‘thing’ to be my father.”

His twinkling eyes darted their gaze from one woman’s face to the other: to meet contempt from Mary and astonishment from her Aunt. “If I am right, ‘it’ is sure to come here to see and perhaps devour his son; so should it arrive in my absence, please receive him hospitably. If he’s hungry, offer him Ruth as a snack.”

With every evidence of glee, he went.

“Well, of all the, well, I never did! Does he call that being funny? And why does he walk in that silly fashion? Prancing, I should call it . . .”

Aunt Charlotte continued her harangue without observing that Mary was wrapped up in her own troublesome thoughts . . . THE INEXPLICABLE! Inexplicable indeed! Inexplicable her feelings of foreboding and shrinking when outside that iron-grey façade. Clearly some dumb part of her conscious had known that what lurked behind it was linked to her own fate . . . It was just how, had she troubled to consider them at the time, she might have foreseen events would begin: Aunt Charlotte’s reading aloud this sensational item of news, Aunt Charlotte who thrived on scares and epidemics. So the thing was out—the thing was coming.

“I’d not see it yourself,” Terry had said, “because . . . You know! Might have a very bad effect just now . . .”

Oh, Terry, there’s no escape . . . Don’t you know? I am the magnet . . . I; and what I bear within me . . .

A surge of such black fear swept over her that she had a sharp and sickening struggle not to begin impotently screaming without the power to cease.

And then in sudden reaction, inescapable and welcome, she was laughing at herself for these absurd, outlandish thoughts. Daylight nightmare, due, perhaps, to her state of health. A good thing Aunt Charlotte could not read her mind. The good lady would have a fit . . . She must be strong-minded. She owed it to the second personality forming . . . Did every mother at this period have such a pronounced sensation of responsibility?

Unfortunately Aunt was so given to harping upon a subject and without being either unkind or rude or both one could not check her. On and on she pursued the matter, dealing with it from every angle. And, to do her justice, she was not only apprehensive on Mary’s account, but also deeply afraid herself.

“At any moment you might turn round and find it behind you,” she whispered nervously.

But Terry, looking in, “breezing in” as he himself put it, to a great extent dissipated the unhealthy anxiety of both women.

“It’s been fully realized that the thing’s got to be found and secured. The police are being very active and, if it’s any comfort to you, both approaches to this road are under observation. As you’re nervous, keep your windows closed and both front and back doors locked.”

He stayed some time cheering them up and the thought occurred to Mary what an immensely desirable thing it would be could she by some magic change Vin into Terry. Why had it never occurred to her that he had all the attributes of an ideal husband and father? He’d only been Terry, her pal; never, in her eyes, a potential lover. Yet why not? Especially since, as she now realized, he did love and always had loved her.

That night in Horder’s Cut—an exceedingly narrow alleyway uniting Pool Road and Century Parade—a woman was ripped to pieces. No clue presented itself to the murderer’s identity; nevertheless, little doubt obtained in the public mind. Erne’s freak.

It was all in the paper, which at breakfast Aunt and Mary, coming down together, found Vin reading to the detriment of his food. Without being able to observe visible reasons for her surmise, Mary believed him to be in a state of desperate excitement.

He did not go to work at his usual hour, but began to prowl round the house in a curious, restless fashion. Mary was insufferably aware of him and felt his restless energy inwardly. He roused in her a feeling of hysteria. Screams! Glorious relief . . . Or was it not Vin who disturbed her, but a feeling of imminent calamity? She, too, felt a desire to prowl. From room to room. Away from something? Or because of a desire to know that they retained their normal characteristics—and were empty?

Vin went suddenly. He went laughing. A low, hardly audible mirth.

She sank against the staircase wall, holding her heart.

Twenty minutes later, Terry phoned.

“Seen the papers, Mary?”

“Yes . . . Terry—I’m frightened.”

“Attaboy! Listen, the police have matters well in hand. All special constables are being mobilized and a most intensive search will be made. Moreover, dozens of volunteers are pouring in with offers of help in combing the district. I’m one of them.”

He waited for her reply, but waited so long that at length he asked:

“You still there, Mary?”

“Yes . . . Oh, Terry, I wish you’d be my special constable.”

It was his turn to pause before replying.

“You want me with you, dear?”

“Yes. Especially at night . . . If I knew you were on guard . . . I dread the night. Last night I couldn’t sleep . . . I kept imagining . . . something was in the room. I had to keep raising my head and looking, listening.”

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Vin came home drunk that night. Mary, still looking and listening, heard his entry. He was in his hilarious faunish state . . . She heard him creeping about, sometimes running and breaking things.

The most ridiculous contradictory gladness possessed her. It was good to know that Vin was drunk, breaking things, making comprehensible and unmistakable noise. Anything was better than the early hush during which the foulest danger might be creeping upon her. Here was a danger she could name and understand—even combat. Her soul was still numb with fear of a danger she could not name, could not understand, could not combat.

Far away she heard him laugh outrageously . . . and then a crash. A terrific crash. She knew its nature. Knew as certainly as if present what had occurred. Vin had pushed over the dresser together with its burden of crockery. No doubt he was dancing among the debris.

Simultaneously with the crash, Aunt Charlotte, a sluggish sleeper, woke with a scream of alarm, followed by a cry of pain as she sat up.

“What was that noise?” she asked.

Despite her troubled mind, Mary laughed.

“That noise” was sheer din; but Aunt’s questions seemed to reduce clamour to the scratching of some mouse.

“Vin’s come home drunk and is smashing things.”

“What?”

The older woman twisted to obtain a better view of Mary, whose words she suspected were ironic but as she moved a second crash occurred, whose noise drowned her own fresh squeak of panic. She seemed, however, unaware of her own small outcry in giving her whole attention to the problem suggested by what was taking place below.

“The man’s a lunatic!” she whispered.

“No, just drink-mad.”

“Will he attack us?”

“The door’s locked.”

Aunt Charlotte glanced at the heavy, solid, massive door whose lock was supplemented with a bolt. They were safe. Giantlike strength would be needed to batter down that door single-handed.

“What about Ruth, Mary?”

Anxiety flooded the girl’s mind. She had forgotten Ruth.

“I think she’ll be all right, Aunt. Her door’s thicker than ours and I’ve told her to lock it.”

“Well, pray goodness he doesn’t set light to the house.”

This had been Mary’s fear; but at the moment its significance seemed small. Flames would bring the fire-brigade; fire and numbers would ensure protection from . . . Suddenly she began to doubt her own reason? Surely she must be unbalanced to welcome the thoug

ht of such alternatives!

The noise below had ceased. Complete silence had supervened. Vin was creeping . . . But she was not afraid of Vin, Mary told herself. Violence held little horror for her . . . It was a manifestation of human nature. She glanced at her companion, whose pallor alarmed her. Aunt Charlotte’s face was drawn with pain. She looked exceedingly ill.

“Auntie, is anything the matter? I mean, with you? Are you ill?”

“Never mind me, Mary. I’ve got a pain, but I often have it . . . What’s he up to?” she asked with a wail.

“Shall I go and see?”

“No, no! For heaven’s sake don’t open that door!”

And, as if in justification of the alarm contained in her words, they heard him softly laughing immediately outside their door. Aunt Charlotte rose and, assuming an unconsciously majestic pose, laid her hands upon the water-jug as if it were a bomb.

Strange, slithering sounds succeeded—like hands laid flat upon the wood and moving.

Then this ceased. Silence once more reigned—only to be broken by a scream of indescribable laughter; not near, however. Perhaps from Vin’s own room.

A thud beside her jerked Mary’s mind to things immediate. Aunt Charlotte had fallen, as if dead, almost at the girl’s feet. Symbolic. Her world tumbling about her feet. Devastation that had begun with her union to the wrong man—while the right one looked on.

The fallen woman groaned and opened her eyes just as Mary stooped to feel her heart. She smiled faintly with the courage that all good women, even the stupid ones, have at their command.

“Don’t worry, my dear. Have you some sal volatile?”

“It’s this pain,” she gasped when presently, by her own efforts and with Mary’s help, she had achieved the bed.

“What pain?”

Aunt Charlotte indicated its region.

“I’ve had it for weeks now.”

“You should have seen a doctor.”

“I expect so.”

“I’ll phone for Dr. Grove in the morning.”

“Very well.” She rolled her head restlessly. “Isn’t it very close.”

Echo of a Curse

Echo of a Curse