- Home

- R. R. Ryan

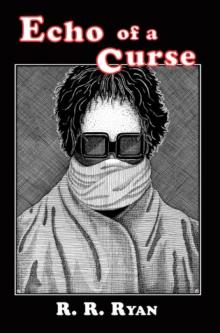

Echo of a Curse Page 7

Echo of a Curse Read online

Page 7

But this indulgence had its penalties, chief among which was the fact that Ruth simply could not keep away from what should have been a forbidden subject—Vin. The dreadful scene still fresh in the girl’s inexperienced mind seemed to have started a complex in her susceptible nature. She told Mary again and again of her stark terror, of her certainty that, whereas she had one instant seen Mary sentient, the next she would see her dead.

And then, quite unexpectedly and very astonishingly, she had revealed that she had seen Terry thrash Border.

“It was terrible, ma’am. He took off his coat, Mr. Terry did, then his shirt and vest . . . He’s ever so strong when you see him, and he struck frightful blows. They seemed to come from the middle of his spine, as if he had a tremendous spring there. And after he’d hit the master again and again, he beat him with the master’s own belt. He howled just like I’ve heard a dog howl, the master did.”

Caught by the girl’s tale, Mary so far had listened, but now she looked up angrily. Yet the anger died as suddenly as it had generated. This telling was medicinal. It was relieving the girl’s mind. Was much better out than in.

“How did you come to see all this, Ruth?”

“The kitchen curtains weren’t quite drawn, ma’am. I’ve always kept the window open till last thing as you told me . . . so I heard . . .”

“Heard?” The question ripped out unconsidered.

“The master and Mr. Terry.” She leaned mysteriously towards Mary and whispered hurriedly, in tones of hoarse horror. “Been in prison . . . and in Borstal. One of our girls had a brother in Borstal; but I never knew anyone who’s been in prison until I heard Mr. Terry tell the master he knew . . . Well, he said it just like this: Borstal, Vincent Border. Three years rape with battery, eh? Eighteen months fraud, eh? . . . I don’t know what he meant by rape with battery. Fraud I know means stealing in a way. But what’s rape with battery?”

As she asked, she looked up at Mary, whose face was chalk while, and her eyes full of horror.

“Oh, ma’am, maybe I’ve said what I shouldn’t . . . I never thought . . . I . . .”

She began to cry. Speechlessly, Mary put out her hand till it lay on the girl’s head, where she let it rest. Borstal. Rape. Fraud. Prison . . . The father of her child. Hate began to merge with horror. She lay back praying almost savagely that the child should never breathe . . . She need not have known. Terry was hiding this hideous truth . . . But better to know! Oh much! . . . All through this child’s prattle, prattle of an over-burdened mind . . . Over-burdened by the same loathsome nature.

They were both silent for a considerable time. Mary, regretting her candour with a domestic, wished that Aunt Charlotte would hurry up and come; but the latter had been inevitably detained by a fire, which, though not serious, had caused considerable inconvenience.

Ruth sat huddled up, staring at the fire, chin cupped in her hands.

“There’s a fair coming to Steadman’s Level.”

The girl’s voice startled Mary, shattering her confused reverie.

“A fair?” she asked absently.

The child’s huge sigh attracted closer attention.

“Yes, ma’am . . . I’ve never seen a fair.”

“You’d like to?”

Solemn eyes, already lit with dawning ecstasy, searched Mary’s face.

“Oh yes, ma’am!”

“Then you shall!”

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

It almost seemed to Mary as if life was to settle down into a kind of humdrum peace. And yet she knew no peace, felt no peace. Vin got a job, through Terry’s agency, as secretary to the Sports Institute; it was one well within an average person’s mental and physical abilities; Vin appeared to be content.

Whenever he and Mary came face to face, his studied courtesy obtained; but behind her husband’s inscrutability she detected, or imagined she did, a curious mockery.

Often she told herself she owed a debt to Terry that she could never pay; but for him, Vin, she felt sure, would have continued to barbarize her; now he had no chance. For the time being, since Aunt Charlotte was not available, Mrs. Thatcher continued to overlook both establishments and was conspicuously in evidence when Border returned for meals or to sleep—which was now about all Mary’s home ever saw of him. Moreover, now every night saw the bustling guardian solidly established in what should have been Border’s own bed, cunningly positioned so as to cut Mary’s bed from direct approach. They kept the door locked, too. Yet, despite all these precautions, Mary never slept without fear in her heart, or with a feeling of security. She was obsessed by fear of fire; but she said nothing of this to anyone, notwithstanding that her anxiety was great. Vin, she told herself with psychic certainty, nursed an all but insane hatred for her, which would express itself sometime in some dreadful fashion. It would be like him, when unbalanced by drink, to fire the place, mocking all consequences, if not entirely oblivious of them. That she was right Border proved three days before Aunt Charlotte was due to arrive. It was Mary’s birthday—though how Vin had discovered this Mary could not conjecture, since she had told none except Ruth. The fair had arrived and was to provide a birthday treat for both mistress and maid.

To this Mary had looked forward, partly because she herself was not far from the age when fairs are more important than affairs and partly because the promised threat meant so much to Ruth of whom she was fast becoming truly fond. And added to these reasons was the all-important hope of a brief oblivion from unhappy thoughts.

But Border saw to it that this pleasant prospect was destroyed shortly before its fulfilment. He sent Mary a birthday present.

There were several presents beside her place when she and Vincent met at breakfast, presents from Aunts, uncles—all more or less remote in her life; there was one from Aunt Charlotte; others from friends; and important ones from Terry, his mother, Mrs. Thatcher and even Ruth; important, not in monetary value but because they were sincere symbols of affection.

However, there was nothing from Vin. She’d expected nothing; would have been surprised had he even known this was her birthday.

And yet the parcels confessed this, so it was not surprising that he should wish her, with ambassadorial solemnity, many happy returns of the day, but truly so when he added:

“My present is not among those others; it’s coming by private messenger.”

Confused, strangely mortified—for she resented that he should assume magnanimous poses—she looked down at her plate while murmuring chilly thanks. He was staring at her. She knew that, even though her own gaze was dropped. And presently, because his stare persisted, she looked up . . . to be quite startled by the malignancy of his regard and by something that she could find no words to fit. Mythological mischief might have been peeping through the leafy shelter of a tree at a chanced-upon victim for whom it had laid a trap; or an afreet have donned collar and tie and a business suit in order to play a non-human trick upon an unsuspecting mortal. The dangerous “naughtiness” of his face was, indeed, indescribable. It was certainly not childlike, yet Mary had never seen it in any adult face.

She said an odd thing to herself:

“He’s got the moon in his veins instead of blood.” And then added: “What an extraordinary thought!”

Vin applied himself to the egg he was eating and made no further reference to his present.

Actually it was as Mary added the last few touches to what preparations were needed for her expedition with Ruth that the latter brought up a little basket—just left by a local boy unknown to Ruth—obviously containing a puppy, a fact Ruth delightedly announced.

“It’s a pup, ma’am!”

It was plain she hoped to be allowed to see the opening of the basket, but some prescient instinct in Mary prompted her to dismiss the girl.

“Go next door, Ruth, and ask Mrs. Thatcher if she can let you have change for this pound note.”

The girl’s face fell, but her training held good; she went.

Despite her appar

ently illogical premonition, Mary felt excited as she opened the basket.

“He knew—I told him—how passionately fond of animals I am,” she thought. “Is this genuine kindness?”

The lid fell back—the little occupant peeped up with pleading eyes. Lovely pleading eyes. Tears rushed to Mary’s.

“It can’t be true! Vin has given me this lovely little thing!”

She lifted it completely out, realizing in sick revulsion it had been foully mutilated. No wonder what should have been a cheeky puppy gaze was mournful query.

Why? That was its question. What have I done? All this world, all this life—and for me, nothing. Why? What have I done?

Gently she put back the injured scrap and re-secured the lid, then ran down to the phone to ring up Terry.

“ . . . That you, Terry . . .? Oh, will you ask Mr. Cliffe to come to the phone . . .? Say, Mrs. Border . . . Oh, Terry. Vincent’s given me a puppy . . . no wait . . . A boy brought it and went at once . . . It was in a little basket . . . Give me a minute . . . my heart’s beating so . . . It’s mutilated; dreadfully . . . No, not a scrap of hope. It must go to the lethal chamber at once . . . You will . . . Ruth and I are just starting for the fair . . . She brought up the basket; but I’ve sent her on an errand. I shall tell her it was dead. She’s all excitement at the thought of a puppy . . .”

“You go to the fair and leave it to me,” Terry told her. “Poor kid! Poor, poor little pal!”

“And poor, poor puppy, Terry! Such a lovely little thing!”

“Don’t let your maid dwell on it, dear. Good thing you’re going to the fair . . . It’s marvellous, I’ve heard. I’ll go myself before it finishes. I have been to see THE INEXPLICABLE . . .”

“What’s that?”

“One of the freaks . . . But terrible, Mary. Not fit for public exhibition. I’d not take that kid. I’d not see it yourself because . . . You know! Might have a very bad effect, just now . . .”

“Very well, Terry . . . Yes, you’re very wise.”

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

How was it Vincent had known to-day was her birthday? She herself had not told him. Certainly Terry had not. Ruth never spoke to him . . . Perhaps the girl had told outsiders; when she was buying her present, for instance. Ruth was often sent on errands to the village. Did she by any chance talk? Sudden alarm rent Mary’s heart. What if she had imparted details of the hideous history that had been made in the Border house since Vincent’s return? Mary glanced down at the radiant, beautifully flushed, Greuzelike countenance now so happily preoccupied. Ruth would not intentionally harm her, or create mischief. But she must make sure . . .

“Ruth!”

“Yes, ma’am?”

“When you’ve been sent on errands, you’ve never spoken about . . . about what’s happened at home, between the master and me?”

“Oh, no!”

“You’ve not said a word to anyone?”

“No, ma’am.”

“You realize, of course, you would hurt me terribly if you did say anything to a single soul?”

“I wouldn’t for the world, ma’am.”

“I’m wondering . . .”

“Yes, ma’am?”

“How the master knew to-day was my birthday?”

The girl made no comment. Mary glanced down and Ruth stared at the contents of a shop window—full of puppies.

“Look, ma’am, puppies!”

“Yes, Ruth.”

“I wish I could have seen yours, ma’am.”

“You wouldn’t, Ruth.”

“Wouldn’t . . .?”

“No, dear.” There was a sob in Mary’s voice and the girl glanced up, grew suddenly crimson and hung her head. She made no further reference to puppies.

Despite the shadow lying between them, they began to enjoy themselves from the instant that they entered the fair ground. It was a very big fair, with novelties and roundabouts galore, most of which Mary and Ruth sampled. Had Mary needed infecting she would have caught the contagion from her wildly excited companion but she needed none. Home, Border, sorrows, everything was forgotten in the delirious joy of whirling, falling, mounting, dipping. They whirled like crazy tops, they fell like shooting stars, they shot up like screaming rockets, they dipped like spasmodic seesaws. They bought and ate roasted peanuts; they bought and devoured sweets. And it was not until Mary came face to face in almost dramatic fashion with a curt but bold announcement that memory reminded her she was a married woman, approaching motherhood, and victim of fate’s cruel whims. They both, as others did, paused abruptly and stared up at the harsh black letters. THE INEXPLICABLE. This side-show stood out from among its fellows by reason of its austerity. A plain, iron-grey frontage lent an air of dignity and emphasized the sign. For those who understood the inference of this sign, the absence of gaudy letterpress and devices doubled their curiosity and accorded the two words sinister import, which was greatly increased when a man came through the turnstile and addressed them. His very manner of appearance held attention: so quiet, so unostentatious, so lacking in all flamboyance. He was tall and dark and grave. An air of power accompanied him. When he spoke his voice was deep, quiet, authoritative; and a slight foreign accent gave it impressiveness.

He was, the man explained, a medical man. He held such and such degrees.

“In THE INEXPLICABLE I offer you true mystery. Is it a wolf? Is it an ape? Is it a demon? Has it supernatural endowment? Is it something possessed? There are those who assert it to be a human being controlled by an evil spirit who torments it at times beyond endurance, so that it screams in some kind of spiritual agony. At times it barks; at times it speaks in diverse tongues. Sometimes it merely growls. I defy the medical men of this town to form any sane opinion as to the true nature of this exhibit, as I have defied the medical men of all the other cities and towns throughout the world. I have traveled with this creature the whole world over, I have been accompanied by eminent scientists; neither I nor they are at this moment one iota wiser than when first I took charge of this living and terrible mystery. Before I invite you to witness the strange behaviour to which at any instant the thing may commit itself, I must warn you that the sight is both morbid and horrific. Those who suffer with weak hearts or nerves, women approaching motherhood and young people are requested to go away. At the same time I must explain that by order of the authorities the exhibit is caged so that no danger shall be run by any member of the public of being torn to bits. Those who have now concluded their inspection are about to be dismissed. The signal will be given when those who wish to view THE INEXPLICABLE may enter.”

As abruptly as he had come, the man vanished; and almost immediately a large number of people began to pour out through the turnstile. It was obvious that twice as many waited for admission.

“Oh, ma’am, can we go in?”

“No, no!”

Mary spoke sharply and turned away. Surely, she thought, if the exhibit were of the nature that showman’s words suggested, it should not be traveling round with a country fair. Clearly enough it paid, but . . . She would ask Terry his opinion. The man’s words had been enough! He had created an atmosphere of sinister danger and unnaturalness . . . There was that in her own home. Besides, standing there, outside that grey, alien façade, an unpleasant sensation of peril had possessed her. If this child was to be her child, she must guard it as hierarchs their sacred secrets.

A sudden overwhelming abhorrence of Border swept through her . . . Hate . . . If the child should resemble him—she’d leave him and the child with him. Otherwise life would be unendurable and the only alternative self-destruction.

She realized now the completeness of the hate and horror with which she regarded Vin, horror dominating hate, horror similar to that she had experienced outside the iron-grey side-show. She could trace a psychological course for this curious association of one impression with another. Anything inimical, anything sinister, anything declared unnatural and forbidding, immediately took her mind back to Vin, thus a

llying him with the example at hand. Wounds, for instance; the mutilated puppy; violence; Vin’s handling of her body; the unnatural: that oddness of aura, glance, physical aloofness that differentiated him from the commonplace.

And at the same time she realized that Vin haunted her. He was never out of her thoughts waking and sleeping. His personality seemed to pervade her house. He had got into the bricks. He was its dust.

A-nature. Dangerous. Blasphemous. He had defiled her by the human act of marriage.

Ruth, she knew, kept glancing up in puzzlement that her till now care-forsaking mistress should be so suddenly gloomy and removed from sympathetic contact . . . Ruth, of course, had not seen that puppy. By now Terry had. What did he think of it? What would he do? Nothing she hoped. There was only one cure for the Vincent Borderization of her life, complete severance of relations; and in so far as she was concerned, was that possible? One cannot shut off memory like a radio—more’s the pity. And the child . . . Oh, no! Better to do nothing.

CHAPTER VI

Aunt Charlotte arrived next morning. It was good, Mary felt, to see her substantial form and somewhat bovine face, though she did not look too well.

“Well, Mary?”

“Well, Aunty darling! So glad you’ve been able to come at last and so sorry about the fire.”

“My luggage is outside. I suppose I’m having the same room?”

“No, Aunty. This is Ruth, who has come in place of Elizabeth.”

Aunt Charlotte laughed.

“Take her place, eh? A little difference between them.”

Like that between leather and swansdown, Mary thought; but she said:

“Ruth knows where to put your luggage. Come into the morning-room until it’s up and have your glass of sherry and a biscuit.”

Echo of a Curse

Echo of a Curse