- Home

- R. R. Ryan

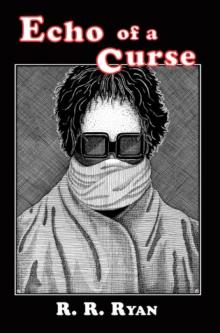

Echo of a Curse Page 9

Echo of a Curse Read online

Page 9

“Yes. A storm coming.”

“What’s that man doing?”

“I imagine his frenzy’s over and he’s gone to bed.”

They listened; but all remained quiet . . . The brooding menace of silence—again.

“Mary, Mary, why ever did you marry him? When will you modern girls learn how much wiser, how much safer, it is to marry the man whose good qualities you know than the romantic stranger whose evil qualities you don’t?”

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Next day there was no news of the freak, so the paper said, and that despite a complete combing not only of the town itself but also of its suburbs. It appeared to have vanished with the ease of mist.

At breakfast Vin received Mary’s entrance with his gayest smile and was his usual debonair and pagan self. He made no reference to the ruin Ruth had reported: pounds’ worth of crockery smashed to smithereens.

“Auntie not coming?” he asked in his politest tones.

“She’s ill.”

“Ill! I’m so sorry. I like Aunty.”

Mary glanced at him. He looked immaculate and cool, yet she herself felt hot, stifled. The thick, sultry air impeded breathing rather than aided it. Her hatred of the irresponsible mimic man opposite her swelled. Had she sense, she’d take steps to protect herself and her home. They were her plates, her dishes, his drunken ecstasies had destroyed. But how could she protect herself without publicity, from which she would shrink at any cost. And of what use to call upon Terry to deal with Vin’s extravagances? What could he do except thrash the culprit and, since that expedient had failed as a preventative, it must not be allowed to degenerate into a medium of revenge: that would be a fresh abomination—on her side.

“Were you frightened last night?” she asked Ruth a little curtly.

The girl glanced askance at her mistress and mumbled.

“You keep you door locked, as I told you?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“I can try and arrange for you to get another situation if you like, Ruth.”

The other burst into hysterical tears, for which she would accord no explanation; and, while Mary was still trying to pacify her, the front door bell rand loudly.

“That’s the doctor for Aunt Charlotte . . . No, don’t you go, Ruth. He’d think I illtreat you. I’ll go.”

Half an hour later Dr. Grove said to Mary:

“Your Aunt is very ill and I’m almost certain an operation’s necessary. She must be very minutely examined and I would suggest her removal either to hospital or a nursing home.”

“Have you told her?”

“She seemed to expect some such opinion and mentioned a nursing home herself.”

“Very well, Doctor.”

“Shall I make the arrangements?”

“If you’ll be so good.”

“Very well, I’ll arrange for her to be moved tomorrow morning, about eleven.”

“Thank you.”

Another prop gone. Another refuge closed. She had depended upon Aunt Charlotte, who, if old-fashioned and a little dull, was, above all else, kind and a most proficient nurse. Was there any danger of being deprived of Aunt Charlotte’s aid when the child was born? That would be a really bitter blow. There was something solid and protective about her Aunt’s ample body and solid sense. Even Mrs. Thatcher would not be so welcome as Aunt Charlotte at that time.

Suddenly she realized with extraordinary clarity what was taking place within her—the production of another human being—and to her amazement a wild pang of love rushed into her heart and tore at her womb. Her child! What an immeasurable compensation if only it were her child; not his, not another sort of satanic imp. She could, then, well afford to ignore Vin and his incomprehensible annoyances. She would love as deeply, as steadily as great rivers flowed to their destiny.

Aunt Charlotte! Poor thing! How the young wrapped themselves up in their own concerns! But who knew what agony and suffering might await Dr. Grove’s new patient in his nursing home?

She must go up and talk to Aunt, explain about the doctor’s wishes and . . . But just then the phone rang. It was the doctor to say that a suitable room at the home would not be vacant until the next day but one; would Mary explain to her Aunt? No, it was not urgent that the patient be examined within so many hours, or even a week; but the sooner the better.

As she mounted the stairs to the invalid’s room, Mary caught sight of the lowering sky through a landing window. Great balls of indigo clouds with nuances of tarnished brass and dull oxide, with occasional bursts of angry silver. The whole sky had a metallic look and a weight seemed to be pressing down upon her head, a weight of compressed, almost solid, air. A forbidding sky. Dangerous. Angry. Full of hate. Full of spite. A tablet of wrathful prophecy—and to Mary of more than harsh storm and deadly lightning. An hour to suit deeds contemplated by something more awful than nature—cruel though that can be.

“Aunt must not get up,” she told herself. “But I don’t think she wants to . . . Let us pray heaven Vin behaves himself until the poor soul’s gone.”

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

“If only the storm would come and disperse,” she cried to the matt agony of her head. “I shan’t sleep . . . I shall just twist about in terror . . . Such a night creates terror out of its own oppressiveness. My head feels full of colourless lead . . . It’s just as if the whole of life’s turned evil . . .”

Aunt Charlotte was asleep. Mary could hear her stertorous breathing. Probably Dr. Groves had put some opiate in that medicine . . . Almost she wished that Vin were in one of his drunken ecstasies . . . Any noise would be welcome. But no noise broke a stillness that to her too conscious mind seemed uncanny . . .

And then there was a noise: muffled tramp, tramp, tramp . . . It died away. Came again. Tramp, tramp, tramp . . . And again. From East to West, from West to East.

Now it was gone . . . She strained her ears hard. Yes, after all this time, again; but from the back . . . From East to West, from West to East . . .

And then once more from the front . . . Now, gone.

Suddenly she understood.

“It’s Terry, keeping guard. Over me! Oh, bless him, bless him!”

The love that she had been suppressing burst through her control . . . He’d be coming round to the back. She’d watch for and signal to him . . . Aunt! Still sound . . . She drew back the blind of the smaller window that looked on to the big back garden . . . How exceedingly dark the night was, a pall, thick, impenetrable. Not a gleam . . . And then she realized her mistake. There were gleams, gleams of light. Two. Tiny, luminous glints. They came from the bushes above the stream. A cat? Then she heard Terry—coming. From East to West. Her blood chilled. Her heart halted . . . Terry coming . .

She saw his torch. He jerked it this way, that, at the bushes whence she had seen the luminous eyes; then continued his march, satisfied.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Mary did not go down to breakfast. Aunt Charlotte was again in pain and needed attention.

“Have they caught that thing, Mary?” she asked between sips of revolting gruel.

“I haven’t seen the paper, Aunt. I’ll go and get it.”

“Yes. I’d like to know. The night was quiet, wasn’t it?”

“Yes, Auntie. Inside and out.”

She heard the rumble of men’s deep voices as soon as she opened the door. Now who? Now what? Definite knowledge that something sinister was afoot grew in her mind until it was a great white certainty.

She ran swiftly down.

Ruth, trembling, crying, her eyes alight with hardly sane horror; Vin, his stance one of some creature overvital and his entire face agleam; a police-sergeant and a constable—these stood an absorbed group in the hall.

As by one impulse and as if one corporate being, they turned towards Mary as she descended.

Ruth, seeing, perhaps, a refuge, or instinctively driven to a fellow-woman’s side, rushed to the new-comer, throwing frantic arms round her.

“Oh, ma’am

, they’ve found . . .”

“That’ll do!” The sergeant’s deep voice boomed Ruth’s hoarse whispering into silence.

Mary felt her whole body blanch, her heart, her very blood must have gone white . . . Terry. They’d found him dead, torn . . .

“This is your wife?” The sergeant asked Vin, sharply.

Mary knew at once he did not like Vin, was prejudiced against him . . . Thought him too flippant in the midst of tragedy.

“Yes, this is the missus.”

Vin grinned at Mary.

A glance at the latter’s face assured the officer that here was a much more estimable type than her wise-cracking ape of a husband. His feelings for Vin were rude.

“Guts all run to beauty, I should imagine,” the sergeant mordantly concluded. Anyway he hated beauty in men. They should be beasts and hairy. He was, himself, and took deep pleasure in scratching his pelt at night. The sports columns called him gorilla, or a great bear; said he resembled both in the ring. But Mary was gentle, almost beautiful, and even during his first glance became beautiful. It was impossible to associate her with deeds of violence, deeds of horror.

“Were you disturbed in the night, madam?”

“No, sergeant . . . At least . . .”

“Yes.”

“I lay awake and heard someone patrolling round the house . . . outside, I mean.”

“Yes, that was your neighbour, Mr. Cliffe, on special duty. You heard and saw nothing else at all unusual?”

Mary faltered.

“I got up and looked out of my window at the garden.”

“Because you heard the footsteps?”

“Yes?”

“Did you notice anything?”

“I saw two eyes, which I took to be cat’s eyes, gleaming from the bushes above our stream.”

There was silence for a while. Vin, Mary thought, seemed almost unable to restrain some secret mirth.

“I regret to tell you that the mangled body of a child was found in those bushes this morning, madam.”

Mary felt Ruth clawing at her arm; terror!

“The freak, sergeant?”

“We assume so, madam.”

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

“P’raps he suffers from a tapeworm, Mary.”

“Who?”

“Terry.”

“Why?”

“To make him so ravenous.”

She stared at his eyes full of brittle laughter, laughter that seemed to gleam and die like sparks from an anvil. She was aware of the venom in her gaze.

“What a pity it was that child.”

“And not me, darling?” He came a little nearer. “I’m tough, pet. Besides, didn’t you know it was my father? Demons aren’t cannibals . . . I shan’t eat our child.” He thrust his face close to hers, so that their eyes almost met. She seemed to be staring into empty spheres, which slowly filled with a glacial light.

Mary experienced an insurgence of boundless contempt.

“His whole mind, his whole being, what serves him for a soul, each is empty and lit by false humanity. He’s just a mean cad! Not dangerous except to women because he’s a little stronger . . . A sham! An actor! He’s trying to make me believe ghastly things about himself . . . An opportunist, that’s what he is. He’s trying to associate himself mysteriously with this escaped freak, because he sees in it a means to terrify me.”

Perhaps he sensed a change in her attitude, for he moved rapidly away. But at the front door turned.

“Quite an epicure, our wandering freak, Mary. Likes them younger each time.”

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

“Nobody can account for how the child came there,” Terry told her. “It came from Platt’s Square, a mile away. It was supposed to be in bed. The parents are utterly mystified . . . It was a lovely child. An only one . . . And I . . . right by the spot . . . On guard till dawn. On guard when it was happening . . . Mary, it’s beyond my comprehension . . . It’s like, like Satanism. Every time I patrolled the back I searched those bushes. My last act before going off duty was to examine the whole garden minutely . . . There was no sign of anything wrong.”

Mary shuddered. THE INEXPLICABLE! How well-named.

Her skin irritated. Prickles, she was all prickles. And every now and then a tiny thread of sweat found its way down her loosely clad body.

“I wonder if I’m going mad?” she asked suddenly, shrilly.

“Now, Mary dear, why do you say that?”

“Because . . . this weather . . . it only began—this unendurable oppression—after that thing escaped.”

“I’d not mix up meteorological phenomena with ordinary events.”

“Ordinary?”

“Well, creatures are constantly escaping from custody. True there’s a sinister element attached to this escape, because no one knows what the thing’s predominating characteristics are, human or bestial. Nevertheless, there’s no other mystery about it.”

“Except how it got out and how it’s evaded capture and how you didn’t come to see it last night and how it contrived to devour a child in my back garden, a child that should have been in bed and asleep a mile away.”

“You’re wrong in saying it devoured the child. It would be almost better if it had . . . We should know then that the creature is brute, not man; that it kills to eat, as wolves kill to eat; but it merely tore the child apart and left it so, as if one instinct defeated another, as if the brute, having obtained its prey, prepared to fulfil its instinct, when the human urge forbade.”

She got up, crossed to the window and stood staring out, up at the sky, which looked to her like embossed copper—and near, even to be deliberately but surely descending . . . She would never drag through this life-squeezing day without some violent personal demonstration . . . It would be possible for her to turn upon even Terry. The violence that was gathering in that savage sky was creating violence in herself. Aunt ill. Stupidly meandering in the way of old and brainless women . . . and night gradually coming; night with its tortures: incalculable beings cloaked by the night with an invisibility that perhaps they did not require; Vin and his orgies; most of all this crushing atmosphere that seemed to grip one’s heart and squeeze it. Inescapable menace.

“Will the police be bothering us?” she asked curtly. However, if Terry notice her tart tone, he ignored it.

“Oh, no! They have definitely decided that the child was killed by whatever killed that woman the other night; and naturally they assume it was this escaped creature from the fair.”

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

As the day proceeded the elements’ mood, as expressed by the ever-lowering sky, did indeed seem to communicate itself to Mary, transforming her from the kindly, happy-tempered woman she normally was, into a being as farouche as its own heavy exhalations. She snapped at Ruth, ignored Aunt Charlotte, lay stripped on her bed fighting for breath, fighting too with a wild revolt against the man who had trapped her with his bond that inextricably united her to him, to that preening fool, that hurtful monkey, that Adonis with Caliban’s nature.

During the afternoon little gusts of wind snapped over the earth. But these were threats. Harbingers of clamour and danger. Swift, invisible horsemen speeding to announce the might of their personal war-gods.

Of course she was full of dread, apprehension; she acknowledged that. Something was coming, some disaster. It was this that so agitated her.

After tea Mary kept going, though the blinds were drawn, to look out of the window—whichever room she happened to be in; for her restless feet took her from this one to that and back to this. Great swollen masses of cloud with burning edges seemed to hang right down from the sky. At any moment one might burst and deluge the earth with its burden, whether fire or water. The compression of air increased. Her lungs hurt. Her heart felt even more constricted.

And then she no longer dared look from the windows, for night was slowly and fully developing; night—with that other menace, for which this impending storm was such admirable cover.

And yet what should she have to fear? Her gardens back and front were fully guarded. Patrols were in the roads beyond. She should be as safe as Royalty . . . But even Royalty, she told herself, is not safe from microbes and other invisible foes . . .

About nine low rumbles began, growls, imprecations, the low mutterings of destructive force . . . She went up to Aunt Charlotte and found her calm, placid, ready to talk . . .

“Aren’t you afraid, Auntie?”

“Of what, dear? Thunder and lighting? No I never minded them . . .”

But then Aunt did not know about the mutilated child, nor had she seen those gleaming eyes. Aunt was old, infirm, ill; she had not in her body another life, something young, lovely or horrible . . .

And Ruth was afraid. Mary saw that when the girl came to say good night. Her cheeks were livid, her eyes black pools of terror. But what could either of them do to help each other, except pretend?

And, underneath all her own fear, she knew her soul was weeping. Life had fulfilled her wish, given her fertility, given her the gift that few women reject and the burden they desire, but not the hope and gladness that should accompany it. Only this dread of her child’s nature, her coming child’s nature.

She would go to bed herself. She would not . . . For, even as her decision was made, a fresh, more prolonged roll of thunder—Cerberus showing his teeth—faltered her steps . . . The little winds came lashing, savage, whispering laughter . . . She went into the drawing-room, drawn by an imperative desire to open the french windows, defy the gathering storm, the night and whatever it might hold. But she could not stay. The hysterical urge in her blood drove her out.

Passing through the hall, Mary experienced a sudden sense of insecurity . . . Rooted, she stared this way, that . . . The front door was ajar. What did that mean? Such a little thing; yet so much. So prosaic; immeasurably portentous . . .

Had Vin come back, drunk, and forgotten to secure the lock and bolts? She listened . . . All seemed still. She might go to his room; but profound reluctance gripped her, even as the thought occurred.

Echo of a Curse

Echo of a Curse