- Home

- R. R. Ryan

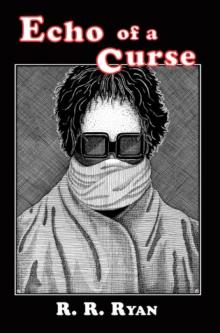

Echo of a Curse Page 4

Echo of a Curse Read online

Page 4

And then this sudden deluge of disaster: not only her own father dead, not only her neat life dishevelled, but Terry also bereaved and left with a disrupted future; to which must be added this strange uneasiness about the consequences of what now seemed a short, sharp, period of madness. Not that she had changed in her feelings toward Vin. Far from it. Her vague alarm persisted despite those feelings. She was still very young and had not thus far preoccupied herself with prudence, method, foresight. She had wanted desperately to marry Vincent before he returned to the risks of war—like innumerable other women—and had done so in youth’s unconsidering way.

But Dr. Rodney’s death had sobered her considerably and left her with a curious sense of responsibility. She had been accustomed to lean absolutely upon her father’s wisdom and support; now he was gone. She had to rely upon herself—or Vin. But the idea of relying upon Vin, for some reason, amused her; or it would have amused her had circumstances been less tragic. It occurred now to her as exceedingly strange that he should have made no suggestion about their future, no explanation as to his means and other affairs. Was that because he feared death, feared no return, would not speak of the future lest there be none? Was he a very superstitious man?

Terry’s father had been Dr. Rodney’s lawyer and now, in the absence of both principals, Mr. Stone, the firm’s managing clerk, had charge of her affairs. It seemed her father had left all unconditionally to his daughter, but that did not say a great deal, for there had not been a great deal of substance for the doctor to leave. The greatly reduced practice was to be sold and, should that yield what Mr. Stone anticipated, Mary would have a small income, barely sufficient to enable her to live in a very modest way providing she continued to occupy the house that was her own property and for which she would not have to pay rent. But this did not trouble her much; Vin, Terry had said, was a man of independent means; they should be very comfortable—rich, if Vin were well off.

And then the armistice, with all its attendant delirium. Jangling peace. Men returning. Soon she would be Mrs. Border in real earnest, not in merely romantic perspective.

“Golly, I’ve wind-up!” she told herself in genuine alarm.

She could not picture herself as a prosaic house-wife with domestic duties. She still wanted to climb trees, indulge escapades.

And then suddenly she was longing breathlessly, with dry lips, for Vin’s return, magnifying its glory beyond all possibility.

The letter she received from Border announcing his return to civilian life and her struck Mary more on account of its courteous phrasing than because of its ardour. Certainly it was not a lover’s letter.

“It’s the letter of a judicious, meticulous French husband,” she told herself.

This epistle dashed her own high spirits and added to her strange uneasiness. The letter noticeably omitted any reference to arrangements, either financial or domestic. It took for granted that he should rejoin her at the house which was now her own property. Of course, it was understandable that he thought it better to leave all discussion regarding their future until they were again together . . . But one would have supposed . . . London! A spree! Celebrations! Even old Terry would not have proposed so humdrum a reunion. Surely it was an occasion of gladness and extreme gladness should express itself; has to, as a rule.

There’d be no possibility of any “do” at her end. Money was too tight. And that Vin knew. She had written fully after her father’s death, explaining the position, but, though he’d replied, it was only to express sympathy and not to make any helpful financial suggestions. As it was, she’d cut down expenses and imposed rigid economy upon herself, sharing the domestic work with only one maid, Elizabeth, an ultra-respectable and rather ill-tempered person. One maid was not, of course, either sufficient or suitable for a house of any size.

But, of course, Vincent was very young, he’d never been compelled to consider domesticity. From Cambridge to the trenches was poor training in the duties of married life. Things would right themselves.

When he did come, he came alone, unannounced and naturally unexpected.

Mary saw him walking quietly up the gravel drive when she was arranging the curtains at her bedroom window. Attracted by her movements, he looked up, smiling impishly.

“Well!”

Mary dropped the curtains and tore downstairs. He met her with arms rather theatrically outstretched.

“Darling!”

His embrace was fervent yet respectful; the embrace of an actor playing his part realistically.

“Why ever didn’t you wire?”

“I wanted to surprise you.”

“Oh, you have!”

Girl-like she giggled, held him at arm’s length, inspecting—what: lover? husband?

And yet it was all desperately disappointing. When she and Vin had last been together, neither had been normal, but exalted, first by their excited sexuality, second by the fact that his life was in constant danger and this marriage should have been a forbidden thing. But now, this creeping home, this idiotic flat meeting!

“Have you had anything to eat?”

He seemed not to hear and, when she repeated the question, roused himself from definite preoccupation with hardly concealed irritability.

“Oh, yes, yes! Food! Don’t mention it!”

“Is anything the matter, Vin?”

He wrung his hands, rose, walked rapidly about, burst suddenly into tears and sank to his knees, head on Mary’s lap.

She had never had a young man’s weeping head on her lap and felt embarrassed. And, till now, she’d seen no man cry. It made her feel gauche.

“Vin, whatever is it?”

He raised his ravaged face, yet without directly meeting her gaze.

“A most awful thing’s happened to me, Merks.”

Used by now to shocks and bizarre happenings, she waited.

“It’s about the will under which my income’s paid,” he explained chokily.

“Oh!”

She had expected death and disaster, but money! She had all youth’s contempt for money and all youth’s optimism.

“There’s a case in Chancery to decide whether the will means capital is to be paid out or merely the income from the capital.”

“Oh, then you’ll get it sooner or later—your money?”

“Of course. It’s mine, however they decide; but meanwhile I’ve nothing except my demob brass.”

“Well, that’s nothing to worry about. We can manage.”

“But I’ve debts. A fellow runs up accounts without thought.”

“I can lend you money, darlingest.”

“Oh, no! I can get money, a loan from the Jews.”

“You’ll do nothing of the kind, Mr. Border. Mrs. Border’s going to have something to say to that. Good lord, what’s the good of marriage if you can’t lend your own husband money? And it’s not as if you can’t pay it back later.”

“No, that’s true.”

“I’ll have to write you a cheque.”

“There’s no hurry.”

“Well, I’ve got to go to the bank myself to-morrow, suppose I draw out extra?”

“Angel!”

“How much, a hundred, two?”

For an instant he closed his eyes. The corners of his mouth twitched a little.

“Two,” he muttered.

“Poor boy,” she thought, “he hates talking about it.” Then added: “Terry said he was sensitive.”

She liked him better for all this. Found it touching that he should cry because he was letting her down, and felt comfort in this lovely explanation of his drab creeping home.

They had a second honeymoon that night and she responded to his overtures with a spirit, a passion, that surprised him and disgusted her. He seemed to appeal to a vulgarity that she had not suspected existing in her abstract composition.

“It’s coarse, this much-vaunted relationship. No wonder most people never want to discuss it literally.”

A little more

and it would be repulsive, horrible. Her heart beat wildly all night long—while he slept, looking as if material pleasures had never sullied his soul; looking like an embodiment of the aesthetic. Curiously, as curiously as suddenly, she wished it were Terry who lay beside her. Not this erotic stranger, this mystery who filled her soul with doubt, even while he filled her body with ecstasy.

The next day she gave him the money, which he received with gentle diffidence. His conduct was as correct as a pattern. They had three cosy, lovely, days, during which her fears began to melt away. Nevertheless, there was a certain sense of disappointment, a sense of loss inseparable from even these three special days. A sense of something lacking that Terry had unconsideringly and certainly unconsidered supplied. There was a racy tang to Terry that one missed from Vin’s mere brilliance of physical glamour and mental charm. Definitely he was not intellectual, which that much-missed friend was. Moreover Terry had masses of information packed away in his mind and a manner of imparting it that was without a trace of didacticism. No tramp with Terry had ever been boring, whereas she and Vin spent half theirs in silent fatigue.

And it began to dawn upon her that he was unwholesomely erotic, prone to sudden and embarrassing impulses. These manifestations alarmed her. Was this a phase, or did he expect permanent gratification of a similar unlicensed nature?

Then came the fourth night.

Vin had been particularly charming all day, if a little too inclined towards sentiment. He had discussed the future.

“I suggest staying put,” he told her. “At least for a time. We can always travel.”

Mary indulged a thrill of glee. Travel! All the world’s high-spots. So wonderful to her, so casual to him!

“This is a topping home,” Vin continued. “It’ll be nice living next door to Terry. You have a big circle of friends. I haven’t enough money for us to live a real crackajack sort of life among the swells, and it’s better to be a brass-hat in your own home-town than a trooper in Mayfair.”

Mary was surprised at the commonsense of this outlook. One did not usually associate Vin with practicality.

Already, he told her, he had made friends, got to know “some of the boys.” Who these were she did not know and could not imagine; but being so young took things for granted.

At luncheon on the fourth day she said:

“I’ve promised to sing at a concert for the wounded to-night. I have done every week. You’ll come, won’t you?”

“No, not to-night, Merks. I want to get away from anything to do with military service.”

She felt disappointment, which showed in her face.

“It would be a splendid opportunity for you to get to know people. Many of my friends will be there.”

“All the local swells, eh? Don’t press me to-night, baby. Leave it till next time.”

And that was that. She suspected there was an immense obstinacy under his easy manner and insouciance. It appeared that there was some club which he had joined. What its nature or importance were she could not gather and hardly as yet felt justified in criticizing his conduct. So that night they went each a separate way. She to her wounded; he to his “club.”

Since her father’s death and the revelation regarding her financial security Mary had dispensed with the late doctor’s car and, like other unfortunate people in the big town, had to depend upon buses to take her here and there. To-night’s concert was being held at Great Hill’s Top—a threepenny bus ride. Concert done and Mary homeward bound, she preferred to sit on the outside of the bus, since it was a beautiful night, boon and mild. She gazed about her from right to left, left to right, getting peeps into variously furnished homes, into bar-parlours, smoking-rooms, saloons. In the smoking-room of Century’s she saw her husband holding a peroxided woman in a lascivious embrace, while a circle of apparently semi-drunken men applauded. Her blood seemed for an instant to stop coursing, her heart to stop beating, her lungs to stop functioning. Then her blood flooded madly, hot as fire through her veins, her heart bounded in her breast, her lungs pumped dangerously. Infinite impulses, all contradictory, set her body twitching. She should jump off the bus, burst into that room. No. She would never see Vincent Border again. Shut the door in his face. She would vanish. She would—this, that and the other . . .

But she consummated none of her resolves, instead went stonily home, wrote a note bidding him keep away from their mutual room, put this where he could not fail to see it on his return—providing he could see anything—went to bed and locked the door. In bed she drew the clothes completely over her head so that she could neither see nor hear; but despite this the vision of that woman in his arms, his lips glued to hers and their bodies plastered each against the other, remained; and she heard again and again his oft-repeated assurances of love, admiration and utter loyalty.

She heard him come in—the front door crash.

“He’s drunk!” she thought.

Not two minutes later he was smashing at her door. Eyes wide, the hollows under each cheek-bone intensified, abruptly she sat up and watched the door, mute, stone. His voice, continually objurgated her in the foulest terms picked up, she supposed, among the mire and entrails of war.

His tones rose—a crescendo . . .

His crashes on the panels must eventually do several things: split them asunder, rouse the night, terrify Elizabeth, a nervous woman. Her own anger flamed. The drunken beast! What manner of a woman did he take her for? What sort of house did he suppose he was in? Some continental brothel?

Tall, taut, she strode in two strides to the door; she flung it open.

His eyes glazed, unfocused, together with his unreal stance, gave him an air of being detached from his normal human self. He had stepped out of the exact. No demon could have been less of the earth. Not a man, an apparition. Occult.

Held, appalled, ice-cold, she stared, waiting. He advanced in the manner of some automaton and very slowly his lips flowed into a smile, like a snake emerging from sand. Unconsciously she backed . . . What did this mean, insult, assault, death? Blood? Murder?

Then she could not back any farther, unless dematerialization of solid matter miraculously took place.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

With a single fast, deft clutch he tore off the pretty bridal nightdress and laughed with drunken lust . . . Her struggles brought froth to his lips. Deliberately he leaned back and struck her on the mouth, cutting it. Terry had once written, and destroyed, poems about her mouth. Justified inspiration . . .

With a lithe movement, she twisted free . . . But he caught her, his flaming eyes agleam with some sort of phantasy. Captured again, she felt her knees weaken with despair. As useful to protest to some obscene flux! . . . Pinning her flat to the wall with one hand, with the other he picked a pin from its tray and thrust it as far as the head into her white shoulder.

She screamed and battered at his face when she realized he was feeling for other pins; then, fighting madly, tore from his grasp—out of the room, he pursuing. Relentless, silent, intent; wearing his fixed, mischievous smile, which lent his beauty the cast of a bacchant. In the hall, redolent of middle-class calm, he caught up with Mary and snatched her two white wrists, pinning her arms behind, and, heedless of writhes, screams, tears, dragged her to the still unfastened door . . . He flung her out into the night. She crashed down the six shallow stone steps and lay, like a nude, white goddess, on the dew-wet gravel.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Elizabeth, chalk-white, watched from the shelter of the first landing his grandiloquent return, Puckish triumph in face and gait.

He emitted an idiotic, eldritch screech at sight of her and leapt up the stairs. She flung herself through the first door that offered, marked with two Victorian survivals, the 3rd and 23rd letters of the English alphabet, crashed to and bolted the door in his grinning face. He stood, swaying, with one brow cocked up and his falsely direct gaze fixed on the two rude letters. Presently he began to laugh and shout improper remarks at the imprisoned woman; but s

uddenly slumped, fell in a heap, back against the door and asleep.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

It began to rain; a little keen wind crept and gambolled. Mary shuddered to consciousness, then to awareness. Pain enveloped her. One hip was gashed and bruised. The tendons of that leg were strained; the shoulder Vin had pierced hurt acutely; her cut mouth stung; each wrist felt broken; her whole being ached—yet obviously she could not stay naked on the gravel of her respectable little drive. The night still shrouded her shame; there was still time to gain shelter before scandal was assured.

Forcing herself to hands and knees, she looked and listened; but saw and heard no sign of Vin. Little by little she dragged her battered body up the stone steps, once used out of surgery hours by her father’s trusting, cut-to-pattern patients. Mrs. This was ill, Mr. That had suffered injury, could the doctor come at once?

She’d have given a slice of life for Terry, who would at any instant fight like a Fenian in her defense.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

She saw Vin, but he no longer slept back to the door, he had succumbed to the mat and lay on his side. He snored.

“Who’s that?”

With a start, Mary realized that someone was beyond that door and then who that someone must be; besides, now she recognized the voice despite its low tones.

Echo of a Curse

Echo of a Curse